I really appreciate it when you’ve bought a book and are ready to dive into it, but you’re just not feeling it. You can’t get into it. So onto the book shelf it goes, collecting dust. Maybe even taunting you.

And then, over time, into a different time, you pick up said book again and you dive into this time, deeply. It’s singing it’s message through you mind, body and soul.

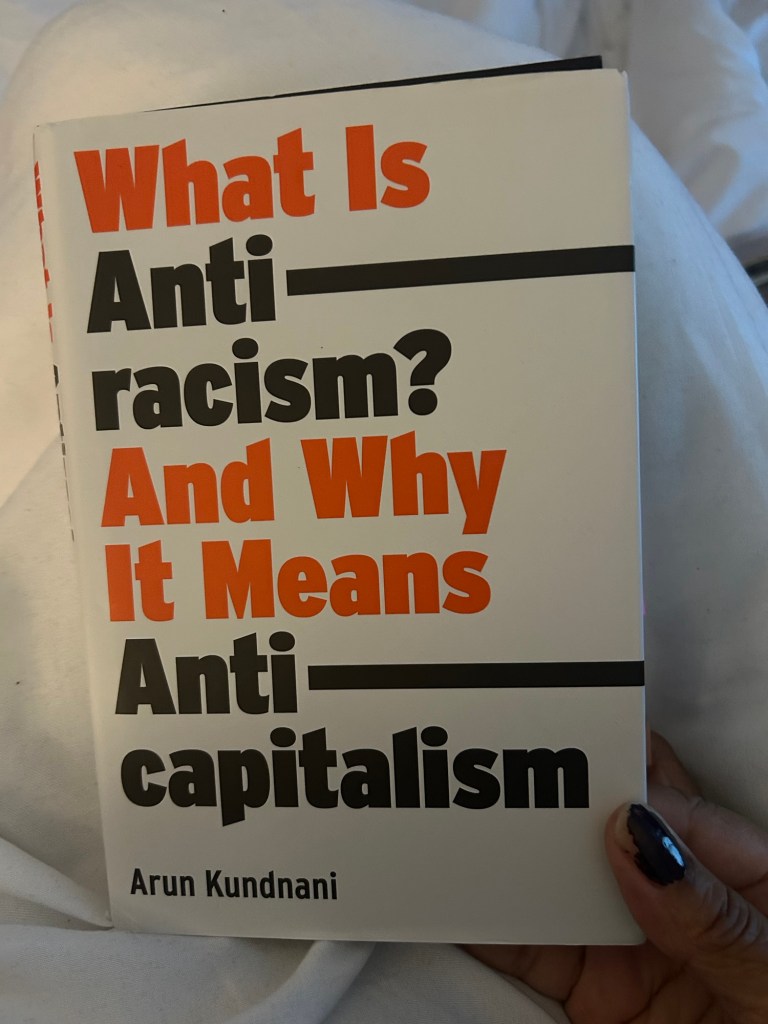

This practice happened for me with Women Who Run With Wolves by Clarissa Pinkola Estes and here it’s happened again with What is antiracism? by Arun Kundnani.

It’s that time of year again where I’m due to go back into Sunderland University and lecture within the Social Work Department around anti-racism. This started in 2020, in the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter uprisings around the world. Up until this point there had been no addressing of race and racism within social work training. And you could still say this is the case as one session, 2-3 hours long, is hardly making a dent into racism and its consequences. But I digress.

Anyway each year, my thinking and practices have changed as I’ve read more and developed more as an anti-racist, anti-capitalist agitator, organiser and activist.

I share my learnings and findings as I want to bring about change for everyone. And this transformation can’t be just limited to working on a personal level as the usual anti-racism training/ education would have us believe.

The problem is not just on an individual level, our unconscious biases etc, the problems are structural and are engrained into the bedrock of our societies, countries and communities.

Anyhow, this book What is antiracism? is not only giving me the historical evidence of racism, the term and practices, but is also sharpening my argument around how racism and classism go hand in hand and that you cannot have a revolution without black workers leading the way. As black workers have always fought for freedom and the dismantling of capitalism for everyone, not just for (white) workers as the revolutions within Europe have done.

We have the French Revolution in the 1700s, lead by the urban masses. We have the Russian Revolution lead by the vanguard party for the proletariat. But we have the Saint-Domingue Revolution in the 1700s lead by the enslaved for abolition of all enslavement in the colonies and Europe, in tandem with the French Revolution happening in Paris. The first time that black and white workers were fighting a common cause together on this scale.

Which revolution succeeded?

The revolution lead by the enslaved, black forced labour, which created the sovereign state of Haiti, a black revolution which had at its heart radical action to transform all societies.

This is what we need now.