I’ve always felt nervous when meeting new people. Not because I’m worried about what they’ll think of me, but because at some point in the conversation I will no doubt be asked the question, “So, where do you come from?”

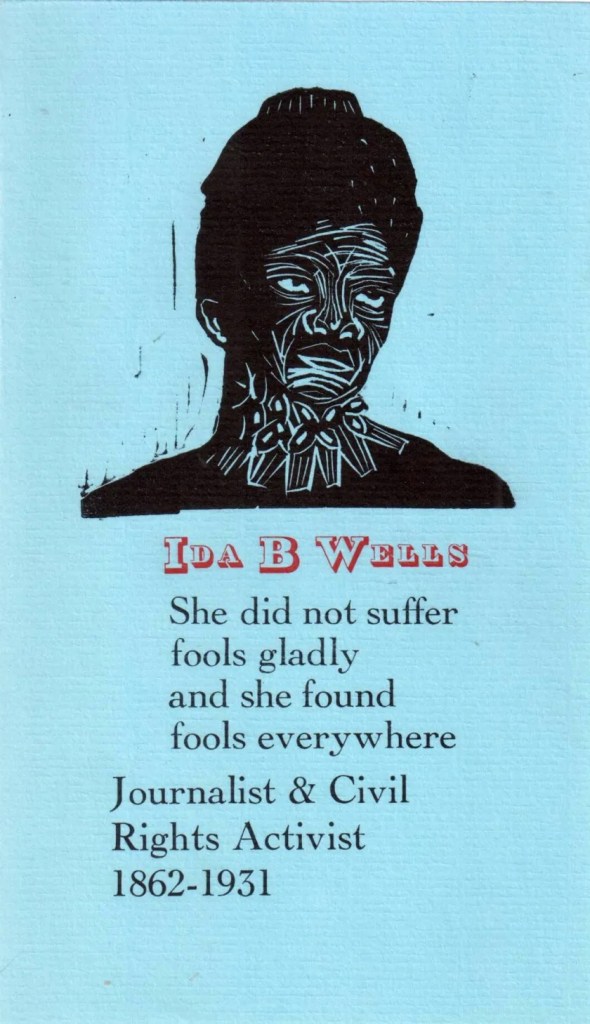

When a white person asks me, this question comes with the implicit assumption that I am not ‘from here’. They might think this is a simple question to ask but it is not a simple question for me to answer.

Should I say Bradford, West Yorkshire, where I was born and brought up until the age of ten? Or the North-East Coast where I live now with co- parenting my daughter? Or even London, where I went to University and got in touch with my ‘black’ side? Or Trinidad, Ghana, Barbados, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone where my ancestral roots lie?

When I was younger in the 1970s and living in Bradford, my dad didn’t talk about Trinidad, but we knew it was the land of his birth. One of the reasons we knew this was because of the black crushed velvet scroll that hung in our front room depicting the islands of Trinidad and Tobago. We didn’t even know he had siblings until, after 25 years of no contact, he received a letter from his sister, Tantie Gladys living in the United States, which started a new relationship with ‘family’.

After my dad’s death in 1981, all the silences changed. Our mum told us the stories our dad had told her but had decided not to tell us about his land, his family, his home. We moved to Newcastle then, to be closer to mum’s family.

It was being closer to my grandparents, listening to them talking and seeing photograph after photograph, that I began to understand my heritage. My maternal great granddad, my nana’s dad, was from the Gold Coast, now Ghana. Charles Mason was billed as the first black man in Newburn, our small village.

I knew that someday I would visit my ancestral lands, Trinidad, Ghana, Barbados, on my granddad’s side, and Sierra Leone and Nigeria, a new piece of information which places my Trinidadian family as descendants of slaves.

“Where will you be buried?” asks a friend. For her the answer is simple; born in England, lives and works in England, dies in England, buried in England. But for me, it’s a tricky question because frankly, I’m not sure where I’m from. I live in Nirth-East England, but I don’t call it home; it’s my base. I wouldn’t call Bradford home, even though I still carry the Yorkshire accent around with me.

‘Home’ as a concept is problematic as it makes visible such notions as gender, diaspora, identity, culture. ‘Home’ as a term includes the sense of ‘knowing home’, what and where home is. It also encompasses that feeling of ‘being at home’ or away from home. But most importantly, ‘home’ includes that matter of ‘belonging’. There are multiple and fluid meanings of home, from private to public, from physical to imagined. The idea of home is plural, a conflicting site of belonging and becoming.

‘Confused’ is one word that should be on my passport.

In 2007, I took the plunge. I approached a visual artist friend and said, “I’m going to Trinidad and Tobago. Want to come?” At the time, I wasn’t sure what I was planning. I was excited, worried, nervous and scared. When I tried to visualize myself there all I could see was the touristy, travel brochure images of the Caribbean; blue sky, blazing heat, turquoise sea, crystal white sands and swaying palm trees. All my knowledge of my heritage was based upon Westernized sources, framing the islands in a certain way.

Having completed a visit to the Caribbean, I can not really imagine what it is/was like to live there, to be born there and grow up there, as my ancestors did. I am second and third generation of immigrants, depending of which side of my family is in focus. I do not have that first hand knowledge of ‘home’, be it the Caribbean or Ghana, but I do of England. As

Avtar Brah says, ‘home’, is a mythic place of desire in the diasporic imagination. Nostalgia is a sentiment of loss and displacement. My experience of my ancestral homelands is limited. In terms of nostalgia, I have a longing for places that are far removed from my everyday but are part of my identity. I may gain an impression of these places through my travels to them or through my family members, sadly all of which are now dead, except my sister. I have that sense of loss of place and of people. I use my writing to create those lost worlds.

There is a photograph of me, in holiday gear (green and white striped top and white cargos), grinning like an idiot, clinging tightly with two hands, onto the arm of a man I’ve just met ten minutes ago in Laventille, Port of Spain, Trinidad. My smile speaks of satisfaction, joy, relief and belonging. This man is a cousin I did not know I had. This embrace is one of ownership. He is family and he is mine. He is part of my past, my present in that photograph, and my future. The past is in our futures, in our nows. I carry with me the baggage of the past into my present and future. My Laventille visit was like going to collect baggage from the left luggage department,finding and claiming baggage that I didn’t know I had lost, but is now vital to me in my task of trying to know myself better.

This feeling of belonging, this split identity/mixedness of being/feeling British, Caribbean, African without exclusive claim to any of them is something difficult to live with, to function with.

This is an updated and redrafted extract taken from my 2010 PhD thesis, ‘A Drift of Many-Hued Poppies in the Pale Wheatfield of British Publishing’ Black British Women Poets 1978 – 2008